Flexibility at work comes with risk?

- David Burton

- Blog

Human Resources Magazine

Human Resources Magazine

EMPLOYMENT RELATIONS David Burton

Flexibility at work comes with risk?

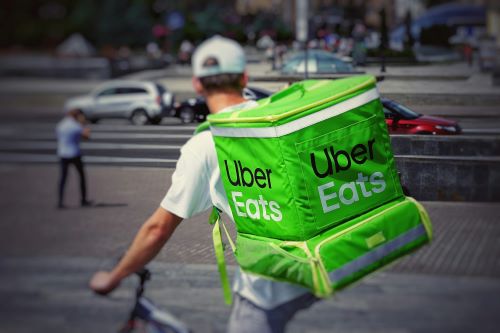

While we await the Court of Appeal’s ruling on the recent Uber cases, David Burton, an employment law barrister, looks at the implications for employers. Achieving flexibility by accessing the so-called “gig economy” may bring some risk.

Generally, the Uber cases reflect a testing of employment status in light of fast-moving changes to the way in which work is done. Most recently, the Chief Judge of the Employment Court in E Tū Inc v Rasier Operations BV issued a declaration that four Uber drivers were employees.

The business model and the law

The Court explained that the Uber operation works as follows: riders/eaters download the Uber App; they advise Uber (via the App) of where they want to travel to/what they want to eat; Uber (via the App) offers the trip/food to available drivers; an available driver accepts the offer, collects the rider/food and drives to their chosen location. Riders and eaters make payment to Uber; Uber makes payment to the drivers.

The starting point is the Employment Relations Act. In deciding whether or not a worker is an employee or a contractor, the Court “must determine the real nature of the relationship”. In doing so, the Court must consider “all relevant matters, including any matters that indicate the intention of the persons” and “not to treat as a determining matter any statement by the persons that describes the nature of their relationship”.

The Employment Court highlighted the need to adopt an approach to determining the status of the drivers with regard to legislation and its role in protecting vulnerable workers and ensuring that minimum standards are maintained. It said that the broader social purpose of the legislative framework must be kept in mind when considering whether a worker is an employee. The Chief Judge said that her task was to ascertain whether the individual is within the range of workers to which Parliament intended to extend minimum worker protections.

The Court’s findings

The Court accepted that some of the usual indicators of a traditional employment relationship were missing. However, it found that significant control was exerted on drivers in other ways. These included incentive schemes that reward consistency and quality. Other controls included withdrawal of rewards for breaches of Uber’s standards, such as slips in quality levels, measured by user ratings.

The Court observed that, on one level, being an Uber driver provides flexibility and choice. Drivers could juggle driving with their other jobs, businesses or family and community responsibilities. None of the drivers were required to log onto the App at any particular time and could work as long or as little as they liked.

The Judge thought that concepts of “flexibility” and “choice” were not particularly helpful in determining employment status. She observed that flexibility is a feature of modern employment relationships. Casual employees, for example, can exercise flexibility and choice about when they work (there being no legal obligation to accept work offered). The fact that they can choose to work at times that suit their personal commitments does not mean their worker status changes. She observed that in New Zealand any employee, casual or otherwise, is entitled to request flexible working hours and such requests can only be denied on a limited number of grounds.

Importantly, the Court said Uber had sole discretion to control prices, service requirements and standards as well as other aspects of the business such as marketing. Drivers were restricted from forming their own relationships with riders or organising substitute drivers to perform services on their behalf.

The cost of defending

In coming to its decision that the drivers were employees, the Employment Court was not deterred by the complex commercial operation that Uber uses in New Zealand. Interestingly, the Court found that an employee may have more than one employer and that an employer may be more than one corporate entity.

When considering flexible work arrangements, employers may need to consider the cost of defending the arrangement. Uber has deep pockets and operates in a global market. It can certainly afford to litigate this issue as far as it needs to (or can). The appeal of the decision has now been heard in the Court of Appeal and the decision will be released in due course. Whatever the outcome, it will be a significant decision. Read more....